Many people ask why Grammar of Grace uses the Geneva Bible for its English Bible translation, which is a bit, err… different for modern readers. Wouldn’t it be better for our children to learn the Bible in the everyday language they’re familiar with?

My husband and I gave great consideration to the question of Bible translation, and—as I explained in the previous article—the main reason why we chose the Geneva Bible is because we think it is the most accurate English translation.

Having made that decision, though, there are many more benefits our homeschool grammar school students enjoy because of using the Geneva Bible, especially when it comes to language.

Let’s start with the most obvious one—the working vocabulary of the average English speaker at the time the Geneva Bible and Shakespeare’s plays were written was about 18,000 words. We know this because Tyndale, Knox, and the other Bible translators of that time were translating into the language that average people understood. And average people did, indeed, buy and read these Bibles. Similarly, Shakespeare’s plays were attended by audiences not just of the nobility, but from the lower classes as well. The working vocabulary of the average English speaker today is about 3,000 words. If our children read the Geneva Bible, they will learn a much richer vocabulary. (And artful use of the language as a whole.)

And while I’m at it, the English of the Geneva Bible is not Old English! And it’s not even Middle English. It’s Modern English. For real. Here’s the way you can tell—Old English is also known as Anglo-Saxon, and you couldn’t even begin to read it; it’s like German or something. When you see Middle English, you see a bunch of words that are spelled wrong but that kind of look like words you might know, some words you totally can’t figure out, and when you put the whole thing together, you have the sneaking suspicion you have no idea what it all actually meant. The English of the Geneva Bible—and the KJV and Shakespeare—may have slightly funny spellings, but it’s definitely the language we know and love; it just constantly reminds us that we didn’t learn vocabulary in school very well.

For example, Genesis 7:18-19. The Old English is Caedmon’s poem-translation; the Middle English is from John Wycliffe’s translation, and the Modern English is from the Geneva Bible.

- Old English: Flod ealle wreah, hreoh under heofonum hea beorgas geond sidne grund and on sund ahof earce from eorðan

- Middle English: The watris flowiden greetli, and filliden alle thingis in the face of erthe. Forsothe the schip was borun on the watris. And the watris hadden maistrie greetli on erthe, and alle hiye hillis vndur alle heuene weren hilid;

- Modern English: The waters also waxed strong, and were increased exceedingly upon the earth, and the Ark went upon the waters. The waters prevailed so exceedingly upon the earth, that all the high mountains, that are under the whole heaven, were covered.

So the Geneva Bible’s language is more beautifully written than what we would see written today, and with a richer vocabulary, but it’s totally the same language we speak!

And speaking of more beautiful language and richer vocabulary—the fuller vocabulary carries more meaning. I’ll give you a few examples.

The Geneva Bible uses thee and thou, but it also uses ye and you. Because they mean different things. Seriously! Thee and thou are the familiar form of address; they’re how family members talk with each other; they’re also singular. Ye and you are how people who are not close speak to each other; they’re more formal and indicate respect; they are also the plural form. So the Ten Commandments are less like a formal legal code given by a king, and more like the commands a father gives his children. Modern English translations lose those sorts of distinctions entirely.

Funny words like wherefore mean something. It could be very accurately translated as, “because of this thing, this is what follows.” We usually substitute why in the place of wherefore, because we simply have no concise way in modern English of conveying that meaning, but why doesn’t exactly mean the same thing. It doesn’t indicate the thing that has just previously been said and directly connect it to a conclusion or consequence that is to follow. Words like wherefore, that we’ve dropped from our common usage, were very useful for saying a lot in just a single word. In other words, dropping 5/6ths of our working vocabulary has made our communications with one another less clear—more vague.

Froward is another example. Proverbs 2:15 speaks of men who are froward in their paths. The word is like toward; you might go “to and fro”; froward is like saying “away-ward”. These men are choosing their direction in life, specifically to go away from the Lord and his laws. We have no effective way of saying this in today’s common speech. So—as far as learning language goes—the Geneva Bible gives a far better education than one of the 900-or-so translations that have come out in the past 50 years.

Some argue that the whole point of translating the Bible into one’s own language is so that it won’t be in a different language from the everyday language of a people. And there’s a lot of validity to that argument. In this case, I point out two important things, which caused me to weigh that argument a little less heavily.

First, one of the things Bible translators often have to do in bringing the Bible to a new language is to invent words that do not exist in that language. Pagans often do not even have words for ideas like redemption or grace. And many of the words that have been dropped from common usage in English over the past 200 years are words that explain the Christian faith. Atonement, justification, repentance, propitiation—these sorts of words teach different things about the glorious Gospel of Christ, and we are the poorer for not having them in our daily speech.

Second, I learned all of my memory verses in KJV English as a child. And not only did it not hurt my understanding of the Bible—I believe it made me understand the scriptures better. Not right away, mind you! There were definitely plenty of words I didn’t understand as a child. But it was just like learning all of English in childhood—of course I didn’t understand every word when I was young. As I grew up, and into adulthood, those words were all part of my understanding of the English language. I came to understand all of these scriptures, just like I came to understand words like photosynthesis. And it definitely made me smarter and better at the study of English, literature, and even foreign languages.

When we were first considering switching to the Geneva Bible from our beloved NASB, my husband was suspicious about the thees, thous, and thithers. He’s not from America, and didn’t even have the cultural familiarity with King James English that we have. I suggested that I thought he would get used to it. And he quickly did! We still enjoy the novelty of the translation, and get a good laugh over things like Abraham’s and Sarah’s being “stricken with age”, but we look up words we don’t know, and for the most part read without any difficulty.

And, by the same token, we have no difficulty reading The Pilgrim’s Progress, Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, or the many, many other important writings of the Reformation era. Well… we do have trouble; we did go to public school. But they are within our reach.

The Geneva Bible is a really, wonderfully accurate translation. But it’s also fabulous for training children’s minds, our secondary goal in Grammar of Grace. And it can’t be beat for teaching language arts, perhaps the most important of our third-tier, subject-specific goals.

Did you memorize lots of scriptures using an old translation like the KJV, as a child? How did learning that language in childhood affect you?

Thanks for dropping by; please keep us in prayer!

Recommended Resource

-

Grammar of Grace

$89.00 – $148.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Kim

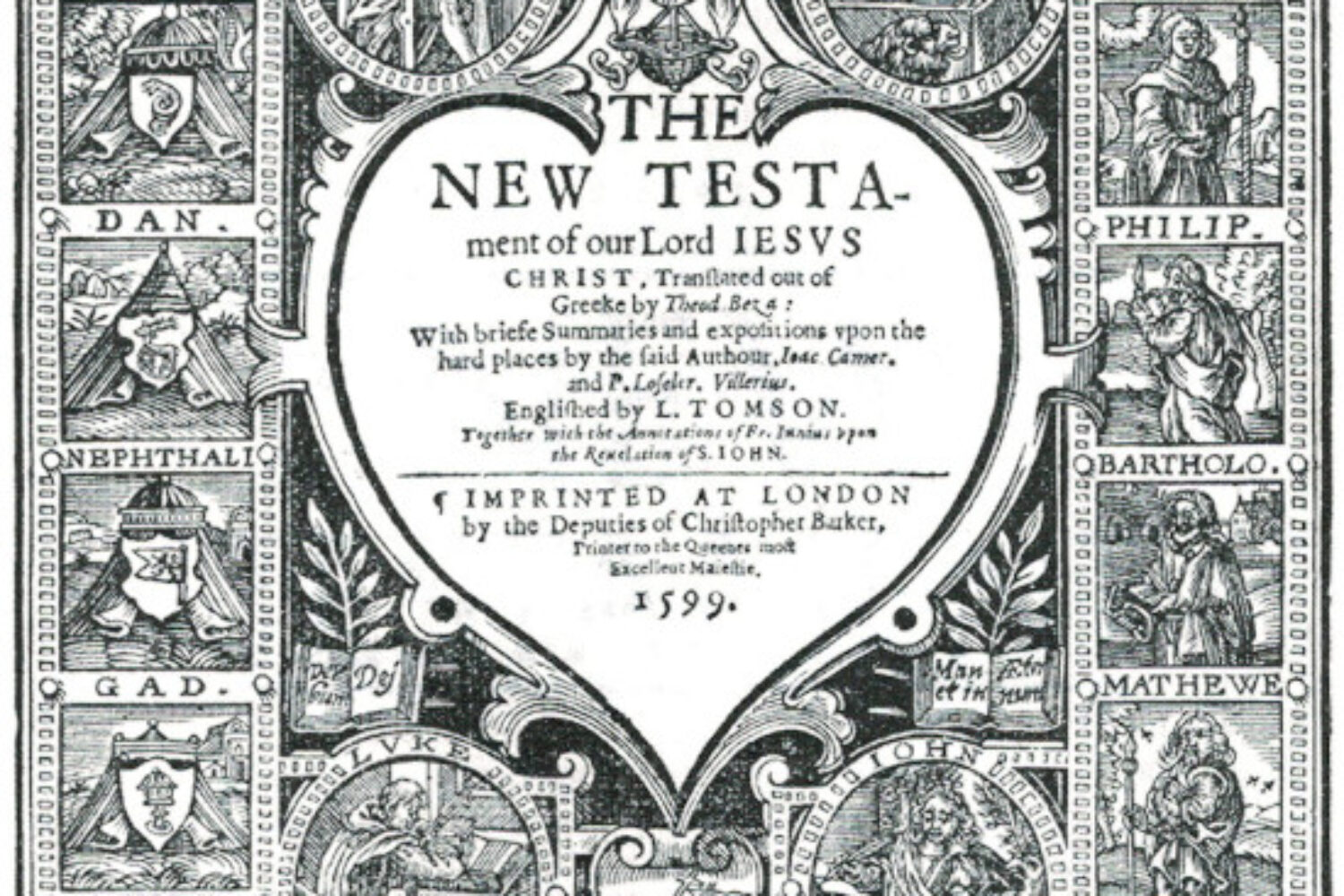

Is there a difference in the 1560 and 1599 editions of the Geneva Bible? Do you have a recommendation on which is better?

Robyn Van Eck

The differences in the biblical texts are minor. I have a 1560 facsimile Geneva Bible, and I love it; my husband and children all use 1599 Geneva Bibles, and that’s what we use for homeschool, too. When I was looking into them, I had the same question, and I couldn’t find good answers, so I’ll tell you the stuff I wish someone could have told me, back then.

The biblical text itself, like I said, has only very slight differences between the 1560 and 1599 Geneva Bibles. I figure that the men at Geneva thought these changes were improvements, so they’re probably for the good. In our family, we usually find that when there are differences, the 1599 is easier to understand. Most of the verses are exactly the same, and when there is a difference, it’ll usually be something like only one word. I’ll give one example.

In Genesis 2, verses 21, 23, and 25 in the 1560 Geneva Bible read:

And in the 1599 Geneva Bible, they read:

The other verses around there are exactly the same.

From what I’ve seen available today, there are a couple of publishers putting out facsimile editions of the 1560 Geneva Bible. Facsimile means that they took an original 1560 Geneva Bible (usually more than one, because some of the pages will be in such bad shape that they can’t be used), and carefully scanned in every page, and then print the whole thing up like that. I like it, because it looks the same way the Geneva Bible folks like the Pilgrims actually used. And it’s got all the beautiful maps, diagrams, pictures, decorations, and everything else. I’ve got the Hendrickson one.

But there are some tricky bits about it, that were an absolute deal-breaker for my husband! First (and worst), back then if an s came anywhere other than at the end of a word, it looked just like and f that somebody forgot to cross. It makes for some really funny reading, like instead of “Hearken unto the wise man,” it reads, “Hearken unto the wife, man!” if you’re not used to it. I’ve gotten many a good laugh over it.

Also back then (just like in the New England Primer) the English alphabet only had 24 letters back then―I & J were considered one letter, and U & V were considered one letter. They used them all of the ways that we write is, js, us, and vs, but they had some sort of rules for it that got them all mixed up (to our eyes). So Proverbs is “Prouerbs”, and Prouerbs 7:27 reads, “Her house is the waie vnto the graue.”

There’s also a notation they used a lot, where if a word has an n or an m, under certain conditions, they just stick a wavy line over the letter before it, and leave off the n or m. That one took me a long time to figure out, lol. Another thing they did was, instead of writing “the”, they often wrote a y with a small e above it, and a few other little things like that. The font is also, obviously, old fashioned-looking.

As for the 1599 Geneva Bible, the only one in print today, that I’m familiar with, is the one put out by Tolle Lege Press. Instead of a facsimile, they copied the whole 1599 Bible, word for word, and set it all in modern font, fixed archaic spellings, and made it entirely readable for modern readers. It still has all the thees and thous, but if the original 1599 said “foole”, the Tolle Lege one spells it “fool”. They did a wonderful job!

There are a few other differences between the 1560 and 1599 Geneva Bibles: First, the margin notes are short and to the point in the 1560, whereas the 1599 notes are more comprehensive. In the 1560, all of the notes are in tiny print, and they actually fit in the margin! But as the years went on, the men in Geneva kept expanding them, until, by 1599, (especially in Paul’s epistles) the notes might even take up more space on the page than the Bible text itself! In our family, we have found these notes to be most helpful; I sometimes grab one of the other family members’ Bibles to read their notes about a tricky passage. Still, even though the 1560 notes are incredibly brief, they get right to the point and usually get the job done.

Second, there are some extra materials at the beginning and end of these Bibles. The 1560 has a few letters I loved reading, and four tables in the back―Bible names and their meanings (to help parents pick good names for their children, lol; was this the first baby names book?!?), a concordance “of the principal things that are conteined in the Bible”, the “years and times” from Adam to Christ, and a timeline of Paul’s life and when his epistles were written. The 1599 Tolle Lege Bibles (at least the bonded leather ones) have the one of the original letters (the better one), instructions for “how to take profit in reading of the holy scriptures”, and forms of prayers. We thought these were really good. If I had my druthers, I’d want all of these things to be in both of the Bibles, because they’re all great Christian teaching, and great history. Tolle Lege also added some good historical articles and a Glossary of some of the difficult 16th century English.

Finally, the 1560 facsimile Geneva Bible contains the Apocrypha―with the original Geneva Bible introduction explaining that these books are not to be read or taught from at church, nor used to prove doctrine, but that they are books written by godly men, useful for learning more history and godly manners.

So, those are the main differences. The 1560 facsimile version looks all cool and old-fashioned, and it has all the beautiful maps and pictures and diagrams (some of the Tabernacle diagrams are the most helpful ones I’ve seen!). Since I can dig the ancient spellings and stuff, I prefer the 1560 facsimile Geneva Bible. But for a foreign-born husband, or children (or anyone else who’s normal), the 1599 Geneva Bible put out by Tolle Lege Press is probably the way to go. We have one for every family member (and it’s on Bible Gateway), and they see much profitable use. I hope that helps!

Tiffany

This was so helpful! Do you have a picture of your Bibles as the links don’t work anymore

Robyn Van Eck

Hi Tiffany, here are links that will take you directly to the publishers of the ones we use. At this writing, both are still available! 🙂

https://www.hendricksonpublishers.com/

https://tollelegepress.com/

Naomi

Thank you very much for this Robyn! Super helpful! I also have the 1560 Hendrickson version and I love it! I’m still getting used to the funny spellings of some words and the notation but it’s really cool too. It makes me feel smart once I figure out what’s written haha. I love that it looks old-fashioned and I also really enjoy the footnotes. Thanks again for this site. This is my second time coming to it, so I wanted to leave you a comment. I’m sure I’ll be back again! God bless.

Ricardo Sava

1599 GENEVA BIBLE is quite perfect, indeed. I agree totally. That’s the one which I wish I got, for i’m disappointed with these modern versions in English that I owned and have ever read. neither in Portuguese, my native language, 1ce I’m from Brazil, don’t I like it very much.

Ethan Sowersby

Hey Robyn, I had a question. I got a 1560 Geneva Bible for Christmas, had been wanting one for a few years because I’d heard the footnotes were jam-packed with good theology, but now that I’m reading it, I’m stumbling over some of the grammatical features. E.G. Genesis 23:3 "Where it says that Abraham rose up from…" and then there’s a weird little character with a lowercase "v" and a small printed lowercase "e" on top of it. Later, in v8, there’s a lowercase "y" with a small "t" above it. The rest of the chapter has several similar constructions with a lowercase "y" with either an "e" or a "u" or a "t" above it. I cannot for the live of me figure out what this means, and I can’t find any answers on google, and my browser’s ai search helper is also stumped.

If you use the 1560 regularly, I’m hoping you understand what these mean, and can give me some insight.

Robyn Van Eck

Congratulations! I got mine as a Christmas present, back in the day, too; must be the best Christmas present I ever got; definitely the most-used!!

I felt just the same way when I started reading mine!!! But once you "break the code", it really gets easy. The old type used abbreviations for the most common words. (I believe it was to save ink and paper, which were outrageously expensive in those days. But also, this was the first study Bible, so they were innovating the idea of having margin notes, and were trying to pack a lot of information into a small space.)

Let me started by "translating" the note for you, and highlight the words with symbols that need explanation: "That is WHEN he had mourned: so THE godlie may mourne, if thei passe not measure: and THE natural AFFECTION is COMMENDABLE."

WHEN: The squiggle above the E is called a tittle (as in, "not a jot nor a tittle of the law shall pass away"). I believe it can stand for either an N or and M that would come immediately after the vowel over which it’s sitting. Sometimes they look a little different, so maybe N tittles and M tittles are slightly different? But I’ve always chalked up the variations to the way the ink was laid down, just normal variation. In any case, you’ll never have any trouble figuring out whether the tittle stands for an N or an M; it’s always obvious which one you need.

THE: This symbol that you described means THE. The y part is a ligature for “th-“, I believe. The one with the e on top stands for THE. The one you noticed in verse 8 with the t on top stands for THAT. And the one with the u on top stands for THOU. It was a space-saving measure, since these words are so obvious/common.

AFFECTION: You’ll see a ligature for -ct-. Learn that one, too.

COMMENDABLE: And there’s the tittle again, this time standing in for m.

I think you managed to find the most tricky bits in a single margin note! I think, with those ones decoded, that you should be in great shape to figure out everything else by context. If you’re already doing okay with the s’s that look like f’s, and are surviving the v’s and u’s that often look opposite from what we expect, then I think you’re going to really enjoy this, once you get the hang of it! And I agree that the margin notes are MOST helpful!! All the best.